A complete concise understanding of the systems approach

When I started this blog (CSL4D, i.e. Concept & Systems Learning for Design) almost 5 years ago (January 8, 2012), I had just discovered concept mapping as a great learning tool. At the same time I had a great interest in systems thinking, but found it hard to get to the bottom of it. So I decided to use concept mapping as the main tool for my pathway of personal learning in systems thinking. This resulted in over 100 posts, 1 book and several (so far mostly unpublished) reports. There is still a great deal to learn, but I think that I have achieved something rather special today: a complete concise understanding of the systems approach in the form of a concept map consisting of 4 inter-related submaps. It is something I have been after – as if it were the Holy Grail – since my discovery of the work on the systems approach by C. West Churchman in 2013 as an essential part of my co-authoring Wicked Solutions, for which I will remain forever in debt to the main author Bob Williams. As to the concise understanding, I am sure I could not have achieved the same without concept mapping. I am equally sure that I will not be able to communicate my ‘discovery’ to you very clearly without the use of concept maps, so I recommend you make a print of the concept map on which this post is based before you start reading. If at the end you decide to quote from this post, make sure you give the full source.

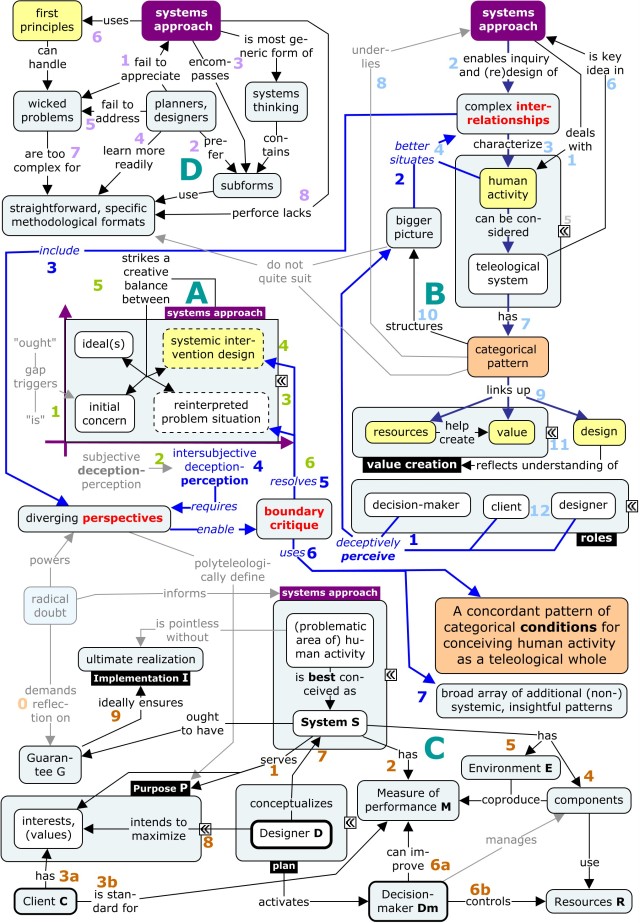

Four sub-maps The four sub-maps are: (A) a summary of need and purpose of the systems approach; (B) the basic categorical pattern for improving value creation (published Oct. 21, 2016); (C) the nine conditions for conceiving human activity as a teleological whole (published Oct. 28, 2016); and (D) the fundamental reason why the systems approach is not applied more often. A detailed description of the sub-maps follows below. In between the sub-maps you will find the relationships between three key systems concepts used in Wicked Solutions to explain systems thinking: inter-relationships, perspectives and boundaries. These concepts have been marked red and have been linked in blue to other concepts or parts in the different sub-maps. If you find the explanations long-winded (the systems approach is not as simple as some people imagine it to be), you can jump to the end of this post where I summarize the lot in just a few sentences.

Sub-map A: informed change This sub-map is essentially a kind of four-quadrant matrix with on the left-vertical axis the level of desirability, where “is” indicates low, actual desirability, i.e. the current problematic situation and “ought” means a future, more ideal situation or a more practical approximation thereof. On the bottom-horizontal axis is the level of understanding, which is low on the left and more advanced on the right. Since we are dealing with complex or wicked problems, there is no full understanding, i.e. all understanding is subject to the principles of deception-perception. In the quadrants you will find four concepts: (1) an ‘initial concern’ that is triggered by a perceived gap between “is” and “ought”; (2) an ‘ideal’ to which you may aspire; (3) a ‘systemic intervention design’, which represents the best way imaginable to approximate the ‘ideal’ in practice; and (4) a ‘reinterpreted problem situation’, which represents the best imaginable problem formulation following increased understanding. The improved insight is the result of intersubjective deception-perception (intersubjective = commonly agreed upon, esp. to achieve the next best thing to objectivity). The idea is simply that sufficiently different perspectives can lead to complementary insights to provide a better understanding of the situation as a whole. The line around the concept for ‘reinterpreted problem situation’ is dotted, because its boundary is subject to critical debate (i.e. boundary critique). In this sub-map the systems approach could be defined as an approach that addresses an initial concern by approximating an ideal situation as well as possible by designing a systemic intervention, i.e. a plan that looks at the whole (also in terms of sustainability and effectiveness), based on an intersubjectively informed reinterpretation of the problematic situation at hand.

Sub-map B: patterned teleology The systems approach applies system teleology to human activity in order to improve value creation. This could be interpreted as a clever answer to a very interesting question, the short version of which is: “What fundamental pattern underlies all human activity?” Or, formulated in another way, “What must we know for studying concerns of effectiveness?“ Human activity is what the systems human-activity-as-teleological-system approach deals with in the broadest sense (1, light-blue). The systems approach provides principles for inquiring into and redesigning the complex relationships (2) that characterize human activity (3). In the systems approach, ‘the bigger picture’ is an important concept, because it is necessary to better situate both complex inter-relationships and human activities (4). Human activity can be considered to be a teleological system (5). This means that human activity is best understood by its ends or purposes. This simple idea is the foundation of the systems approach (6). According to Churchman a common, fundamental pattern characterizes all human goal seeking (7). This pattern underlies the systems approach, i.e. the systems approach explains what the pattern is and what principles must be followed for its application in practice (8). At its most simple the above pattern is the logical connection of fundamental concepts, three of which are: design, resources and value (9). The ‘bigger picture’ is also part of this fundamental pattern (10). The general purpose of human activity could be said to be the creation of value (11). Part of the human activity is the use of resources (and environmental factors) to create value. Another part is design, which attempts to understand what value to create, why, and how. Three roles can be distinguished: the designer, the client and the decision-maker (12). Everything else follows from there, including ideas on planning, effectiveness, management, evaluation etc. But before we get there, we must first take a closer look at the fundamental pattern that characterizes system teleology.

Sub-map C: concordant conditions In Chapter 3 of The Design of Inquiring Systems, Churchman distinguishes nine conditions for conceiving human activity as a teleological system (S, see below concept map). First of all S has a Purpose P (1) or goals or objectives, otherwise it would not be teleological. It must also have a Measure of performance M (2), or else we cannot know how well the purpose is achieved. The purpose must serve somebody’s interests according to his or her values (3a). This somebody is the Client (C) or beneficiary, whose value pattern (motivation, aspirations, ethics, and aesthetic sensibility) is the standard for M (3b). The system has components (4) and an Environment (E, 5), which together coproduce M. The components are managed by the Decision-maker (Dm), who is in a position to improve M (6a). Dm can do so by assigning Resources (R) under his or her control (6b) to be used by one or more components. The Designer (D) conceptualizes the system (i.e. the elements and relations listed so far, including himself and whatever follows) (7) with the intention to maximize the satisfaction of C. This conceptualization is the plan, which activates Dm. D must consider by what Guarantee (G) S can best ensure its Implementation (I) or ultimate realization (9), because without it human activity is pointless. In Chapter 2 of The Design of Inquiring Systems, Churchman develops the idea of Leibnizian ‘fact’ nets after starting his inquiry on the design of inquiring systems with Descartes and Spinoza. The notion of radical doubt by Descartes inspired Spinoza and Leibniz, but also Churchman. How can we know anything for sure? Who is actually the client, who the designer, and who the decision-maker? Who else benefits? Are the roles not overlapping? Are there not multiple clients etc.? Who ought to be the client etc.? What ought to be the measure of performance? What transformation or change do we actually desire? What things outside the system (E, environment) constrain it from delivering its purpose to the beneficiaries? Churchman gives many examples of how these critical questions can lead to surprising and novel insights that can help one to redesign a system (or plan or intervention) and increase its overall and ultimate effectiveness. All other systems or management ideas and concepts can fit into this, so it is a good idea to have the systems approach precede any other systems or management methods. So it should be used a lot. Allow me at this point the interested reader that I summarized Churchman´s philosophical underpinnings of the systems approach last November.

Sub-map D: built-in wicked feedback loop This sub-map explains why (i.e. for what fundamental reason) the systems approach is not used as much as it should. The problem is that the systems approach is based on a number of basic principles as explained in sub-maps A to C. Most planners (consultants, experts, designers) fail to appreciate the systems approach (1, light-purple). This may in part be because they don’t understand well enough how wicked problems are different and why they are important. In spite of the fact that the systems approach is the most generic form of systems thinking that encompasses all sub-forms (3), planners generally prefer to use these sub-forms (2), which they also find easier to learn (4) since they follow more straightforward, specific methodological formats. And sub-forms are not wrong per se. They can be very good for the purpose for which they are designed. Unfortunately, wicked problems are too complex to be addressed (i.e. identified and resolved) using a clear format. Not in the last place because wicked problems are unstructured, i.e. lack a clearly definable problem-purpose nexus to which a particular methodological format can be applied. Therefore, the systems approach necessarily lacks such a clear methodological format (8). The overall result is that most planners fail to address wicked problems in an effective, sustainable way (5). Especially if they are smart. We must raise awareness of this ‘wicked’ feedback mechanism to break the loop.

Wicked Solutions There are two main ways for raising awareness of the need for using the systems approach more often: (1) explaining the necessary logic of the systems approach and why people don’t use it (achieved, see above; just spread the news); and (2) enabling people to apply the systems approach directly to a wicked problem of their own, using a series of steps resembling a methodology, yet retaining most or all of the principles in full that make up the systems approach. This second way for raising awareness has been achieved with the publication of ‘Wicked Solutions: a systems approach to complex problems‘ in 2016. Wicked Solutions is special in the sense that it has simplified the message without losing the essence, i.e. the principles. The simplification involves three concepts (inter-relationships, perspectives, and boundaries) to explain the systems approach while guiding the reader through their practical application. One may wonder how these three concepts fit in the explanation of the systems approach above. To clarify matters I added these concepts (to the extent they were not already included in the sub-maps) to the overall concept map and linked them in the usual way, using dark-blue arrows and numbers: (1) the stakeholders or actors involved each only see their part of reality, but together they can create a bigger picture for a fuller understanding of the problematic situation; (2) this bigger picture (as a step a ‘rich picture’) enables them to better situate the complex inter-relationships that produce the ‘wicked problem’; (3) a key part of these complex inter-relationships are the diverging perspectives (and motivations) of the stakeholders; (4, 5) the diverging perspectives are used in critical debate or boundary critique to gain a better, intersubjective understanding of the many, confusing aspects of both wicked problems and their systemic resolution; (6) to this end use is made of a concordant pattern of categorical conditions that need be satisfied for conceiving human activity as a teleological whole; (7) there is no limit to the (range of tools for gaining) insightful (non-)systemic patterns that may assist the stakeholders in enhancing their intersubjective understanding as long as the concordance between the categorical conditions remains a primary concern. This is the reason why it is unwise to use subforms of systems thinking or other approaches without first or simultaneously using the systems approach (or at least keeping it in the back of your mind).

Systemic patterns There is no end to insightful systemic patterns that can help us understand the many, confusing aspects of both wicked problems and their systemic resolution. A well-known example is that of Peter Senge´s systems archetypes (see e.g. my representation of a balancing system using concept mapping). In fact, my first post was on The Fifth Discipline in Uganda. Looking back at this post, we see that it describes mostly how my interest in the application of systems thinking in the developing world was kindled by a little Youtube film and a slight reference to the use of Senge´s approach to leadership issues. Looking back at the many things I learned about systems thinking in a more distant or not so distant past, I can only conclude that Senge’s approach does not satisfy the requirements of teleological concordance as demonstrated by Churchman. The same applies to many other methods and tools and frameworks (e.g. Osterwalder’s business model canvas). Perhaps all these methods and tools and frameworks together could be reconceived as proto-language of systems patterns (or wicked problem insights and design practices). The original idea for such a language came from Christopher Alexander and luckily brought to me by David Ing. Some ideas for such a language could be gleaned from my post on Rules of thumb and leverage points or from the chapter Expanding your ability to think systemically in Wicked Solutions. But the first thing is to keep thinking by means of our brains, the greatest thinking thing in the universe as far as we know. And to do so properly, let us be guided by the principles of Churchman´s systems approach.

- CHURCHMAN, C. W. (1968).The systems approach. New York, Delacorte Press.

- CHURCHMAN, C. W. (1971).The design of inquiring systems: basic concepts of systems and organization. New York, Basic Books.

- CHURCHMAN, C. W. (1979).The systems approach and its enemies. New York, Basic Books.

Teleological concordance Teleology means goal-oriented activity. Most (but not all) human activity is teleological. Having a goal implies the need for a beneficiary, a decision-maker (to allocate resources to achieve the goal), and a designer (to make a good plan to achieve the goal) and some other so-called categorical conditions for conceiving human activity as a teleological whole. These conditions can be used to generate questions in relation to the effort to achieve the goal, i.e. to move from the unsatisfactory actual situation “is” towards a more satisfactory, ideal situation “ought”. The categories or conditions are inter-related. This means that if you change one category, it has implications for the others. The systems approacher (and the stakeholders in the ‘system’) must acknowledge these implications. This activity is known as ‘unfolding’. Its aim is to make sure that all the categorical conditions work as a concordant whole, which is the overall (categorical?) condition. One of the categories is ‘environment’. The allocated resources need certain environmental ‘factors’ to achieve the goal. A common error in all human planning is the so-called ‘environmental fallacy’, which means that essential environmental factors or conditions are not taken into consideration. It is crucial that the correct relevant elements of the environment are ‘swept in’ to achieve the goal. Similar reasonings can be used for our inquiry into the other categories. This is a reiterative process, because one insight ‘unfolds’ into another.

A man has two reasons for what he does, a good reason and the real reason.

J. Pierpont Morgan

For good measure … just a few remarks about the beneficiary (or client), the decision-maker and the designer (or planner). Churchman understood as no other that with “humans into our problem situation, all bets are off, so to speak” (Hester and Adams, 2014). It are the humans that in most problem situations are responsible for much of the complexity. On close inspection (e.g. using the systems approach or the common sense of Everyman), this appears to be the case even for seemingly simple problems. Without considering the hidden motivations and biases of key stakeholders, it will not be possible to envisage sound and durable solutions. A very simple example will maket that clear. In the case of a policy or project it may seem simple to know who “is” the beneficiary, but on close inspection it may well also be the decision-maker, e.g. if the programming and its evaluation can be manipulated to run ‘hitch-free’. This shows several things: (1) the “beneficiary” (or client) in the systems approach is a role, that can be played by any of the stakeholders; (2) in the ideal case there is ‘concordance’ between the stakeholders about how the role is to be conceived (in fact, in the ultimate ideal case the beneficiary, decision-maker and designer show complete convergence); (3) the application of the systems approach requires general acceptance, not only in the form of ‘good will’ (e.g. to make honest assessments), but also to ensure mutually understandable communication (without which the critical debate will lose all traction). This last point (3) puts the fear into many potential users of the systems approach, but this need not be the case, because: (a) “barking dogs don’t bite”, i.e. the systems approach is not a judicial system, but a system for inquiry and design, where the final design does not normally contain anything harmful to the key participants (or else it would not be sustainable); (b) applying the systems approach takes a lot of effort, which means that it will only resorted to if an activity or plan or policy has failed seriously with no hope for a future turn-around; and (c) for truly innovative solutions it is necessary to dig deep without fear. It is exactly the unsettling part of the systems approach that gets people to think outside the box.